A Knife Pushed Into My Vitals

Railways in Afghanistan, Past and Future

by Andrew Grantham, 2002-2006

Material here is reproduced here on IRFCA.org from Andrew Grantham's web site by generous permission of Andrew Grantham.

On this page

- Introduction

- The Great Game

- Kabul River and Khyber Pass

- A Royal Tour

- Steam Trams in Kabul

- Ambitious Proposals

- Industrial Diesels

- International Plans

- Grand Projects

- Soviet Extensions

- Foreign Advice

- Re-opening for Aid

- Plans Resurface

- Stocklist

- References

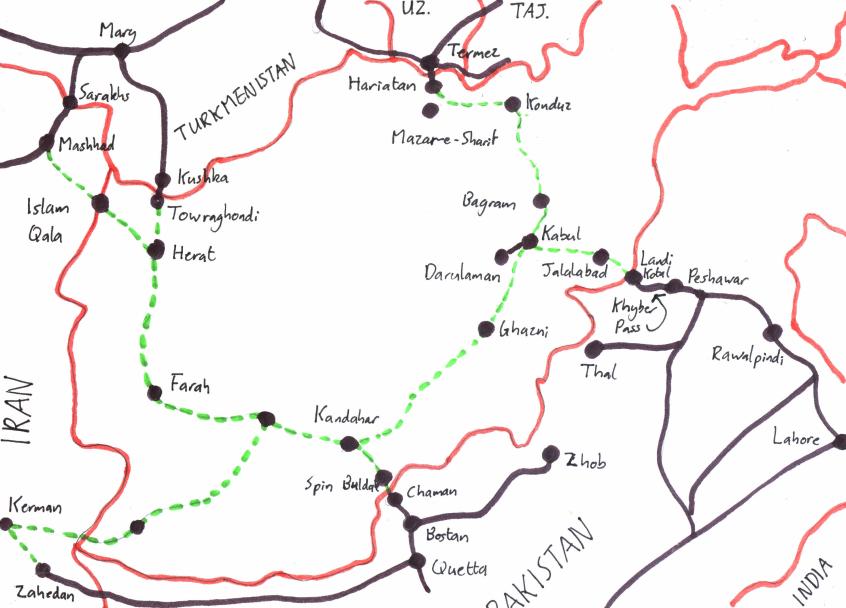

- Map of Afghan Railway Schemes

- Kabul Tramway

Introduction

Other than a few kilometres across a bridge from Uzbekistan, there are almost certainly no functioning railways in Afghanistan today. The country is unusual in that over the years its leaders have often pursued a strategy of opposing railway construction, instead preferring to preserve the country's natural isolation. A number of railways were built towards the country, only to stop short of the border. Despite this antipathy to railways the country has had at least five short lines in the past.

This is a summary of what I have been able to find out about Afghanistan's railways, including those that were only planned as well as those that were built. Even when the lines were operational the region's isolation made details of what existed unclear.

The information is supplied in good faith, but I can offer no guarantees that it is correct. It is far from complete. Much information has been gathered from secondary sources, and I have no plans to visit the region(!). If you have any more details, I'd love to hear from you.

An attempt has been made to standardise place names on the spellings used in Railway Directory 2001[1] or the CIA World Fact Book[2]. This may cause some anachronisms where names and common transliterations have changed. For example, Mary was called Merv until 1937. Most of the areas of India mentioned became part of Pakistan on independence in August 1947.

An earlier, shorter, version of this text formed the basis of an article I wrote for the July 2002 issue of The Railway Magazine. If you would like to use this text elsewhere, please drop me a message first.

Recent news on Afghan railways is on a separate page. If you can provide any more information or corrections, please get in touch with me. I would be particularly interested in seeing any more photographs of surviving remains.

Andrew Grantham

Surrey, UK

The Great Game

During the nineteenth century Britain was concerned that Russia might advance through Afghanistan towards India, threatening British rule in the subcontinent. Britain saw defence of the North West Frontier, now part of Pakistan, as essential to the "Great Game" of politics played across the region by the two rivals.

In 1857 William Andrew, Chairman of the Scinde, Punjab & Delhi Railway, suggested that railways to the Bolan and Khyber passes would have a strategic role in responding to any Russian threat[3]. No action was taken until 1876, when Britan decided to keep at least one route into Afghanistan open all year round to permit the rapid deployment of troops from Karachi to counter any threat to India. Orders were given that a railway should be built to Quetta, near the Afghan border, and this developed into a scheme to reach Kandahar.

The Second Afghan war (1878-80) broke out between Britain and Afghanistan before work could begin. This gave a new urgency to the need for easier access to the frontier, and on 18 September 1879 the Viceroy's council decided to make do with a line through the Bolan pass usable only in fair weather. Work began just three days later, and after four months the first 215 km of the line was complete, opening from Ruk to Sibi in January 1880. On 27 March 1880 the Morning Post commented "after three and twenty years of apathy the necessity has been realised and now these railways are being constructed." The railway was built to the 1 676 mm Indian broad gauge.

Beyond Sibi the terrain was more difficult. Reconnaissance parties had reached Kandahar by December 1879, but Afghanistan was enemy country, making it difficult to find an optimal route for the line. It was realised it would not be possible to for the railway to reach Quetta before the conclusion of the war, and so the railway was given a lower priority. When a new cabinet under Gladstone was formed in April 1880 the planned Kandahar extension was put to one side.

In March 1880 Britain and Persia agreed the Herat Convention. Persia would take control of the Afghan city of Herat subject to certain conditions, including permitting British soldiers to be stationed there. Article seven of the draft agreement stated that

If a railway or telegraph be constructed to Kandahar the Shah [of Persia] at the request of the Queen [Victoria] would facilitate its extension to Herat in all ways in his power and would contribute thereto from the surplus of the Herat revenues according to his ability.

At first the Persian foreign minister requested the removal of this article. He eventually agreed to its inclusion, but objected to the conditions regarding the assessment of the revenue of the city[4].

In 1880 Russia began to build the Trans-Caspian railway[5]. In Britain there was concern that Russia might seize Herat, and extend their new railway to the city. In response to this threat Britain restarted work on the railway to Afghanistan. To avoid alerting Russia to this work it was described as the "Harrai road improvement project", and camels were used for construction traffic instead of the more usual temporary railway lines. This deception was abandoned when Russia occupied the city of Mary in 1883, and the line was developed as the Sind Peshin State Railway. Over 320 km long, the line reached Quetta in March 1887, through barren mountains inhabited by armed tribesmen.

On 30 September 1891 the Chaman Extension Railway was opened, linking Bostan, north of Quetta, to Chaman on the Afghan frontier. The buffer stop lay 5 km beyond Chaman fort, and just 200 m short of the Durand line, the Afghanistan-India border fixed by Sir Mortimer Durand in 1893. A supply depot was set up at Chaman, containing the rails, sleepers and bridge parts required to extend the line the remaining 108 km to Kandahar in the event of a military emergency. Across Afghanistan, the Russians stockpiled materias at Kushka to allow the rapid construction of a line to Herat.

Amir Abdul Rehman, ruler of Afghanistan between 1880 and 1901, banned railways and the telegraph from entering Afghanistan, in case they were used in any British or Russian invasion. Rehman commented "there will be a railway in Afghanistan when the Afghans are able to make it themselves" and said "as long as Afghanistan has not arms enough to fight against any great attacking power, it would be folly to allow railways to be laid throughout the country." Rehman forbade his subjects from travelling on the British line to Chaman[6], which he described as "a knife pushed into my vitals." The Afghan army produced a manual on how to destroy railway tracks in the event of an invasion threat[7].

In 1891 Captain AC Yates wrote a booklet[8] setting out arguments in favour of building a railway to Seistan, rather than Kandahar, to allow the defence of Herat against Russia. "The press and the public are at this moment advocating the extension of our railways to Kandahar; but that this could be done without precipitating a rupture of our relations with the Amir is doubtful".

Around 1910 there was discussion[9] regarding extending the Chaman line to Kandahar, and beyond to Herat and the Russian railhead at Kushka. In the event, the line was never extended across the border. It did however carry traffic from Afghanistan, with a daily ice-packed train bringing fresh fruit grown in Afghanistan to the cities of India until the 1940s.

A through railway link from Europe to India had long been contemplated, but the schemes raised concerns for the security of the subcontinent. In 1910 a Russian syndicate proposed a Trans-Persia railway, running from Tehran to Yezd, Kerman, Seistan and Nushki. This raised the risk of Russian troops being able to occupy Kandahar and Quetta, outnumbering available Indian army forces.

In 1911 a British study[10] looked at the implications of Russian railway construction in the light of the successful movement of troop on the Trans-Siberian line during Russia's war with Japan (1904-1905). The Trans-Persia line faced political problems "in that it would cause alarm and suspicion in Afghanistan, as its rails lead direct to the Afghan Frontier, which may give rise to tribal excitements that may prove beyond the Amir's power to control. The measures taken to restore confidence may involve us in complications with other European Powers."

The study's author commented "No connection between this line and either Afghanistan or Northern Baluchistan should be permitted",

Russian railways now stretched from Orenburg to Tashkent and Samarkand. "The further extension can only be accomplished in peace, or with the consent of the Amir, which is hardly likely to be given; or during a war with Afghanistan. The bridging of the Oxus [Amu-Darya] is estimated to take four months to complete". It was estimated that after reaching the Amu-Darya it would take the Russians 16 months to extend the railhead to Doshi. The report also considered that an extension of the Trans-Caspian railway from Kushka into Afghan territory would only be possible with consent or in war time. Rails were stacked at Kushka, and it was estimated that the line could be laid to the Helmud in 18 months.

"The extension of Russian or Persian railways through Afghanistan should be more strongly resisted than ever" said the report. The author speculated that the German-backed Baghdad railway could be extended to the Afghan frontier, but handwritten annotations on the Public Record Office's copy of the booklet suggest officials thought this somewhat unlikely.

The author concluded that "The present attitude of the Amir concerning them [i.e. railways] may change rapidly, as it has recently with regard to roads in Afghanistan. Thus the construction of these two lines [Trans-Caspian from Kushka, an extension from Samarkand] is probably only a matter of time."

Kabul River and Khyber Pass

During the second Afghan war (1879-1880) Sir Guilford Molesworth considered the possibility of constructing a metre gauge through the Khyber Pass to Afghanistan. However, there was not yet a bridge across the River Indus, and constructing one would have been a major undertaking. In 1885 Captain JRL McDonald surveyed the feasibility of extending a railway to Landi Kotal[11], and in 1890 he surveyed a route along the Kabul River gorge. In 1898 a survey was carried out for a metre or narrower gauge line through the Khyber Pass to Landi Kotal.

In 1901 the broad gauge North Western Railway was extended from Peshawar to Jamrud, and in 1905 work began on a metre gauge military railway along the Kabul River valley in the Mullagori hills.

Parliament authorised the construction of this line as far as Torkham, and there was heated discussion about what course should be taken through the narrow Kabul River gorge. There were two potential alignments. One ran up the Loi Shilman valley as far as the Shilman Ghakki pass, the second route followed the Kabul River to Smatsai, below the fort at Dakka. On 17 December 1904 Lieutenant-Colonel HA Deane, Agent to the Governor General and Chief Commissioner, North West Frontier Province wrote to the Secretary to the Government of India with plans and estimates for the Shilman Ghakki route[12].

Commander-in-Chief Lord Kitchener supported a direct route westwards through the Loi Shilman valley, with a tunnel between Warsak and Smatsai. The tunnel was deemed to be too expensive, and so it was decided to take an easier alignment following the bend in the river to Palosi.

The Afghans considered their territory to extend for some distance on the Indian side of the artificial border of the Durand line. Which ever route the railway took, it would extend about 56 km beyond British-controlled areas. Construction work was held up by local tribes launching attacks on the works. The authorities discussed how best to protect the line, and the Chief Commissioner for police and militia corps on the North West Frontier directed Major GO Roos-Keppel of the Khyber Rifles to prepare a scheme to defend two possible routes for the railway.

Major Roos-Keppel, Major Dundee of the Royal Engineers and Captains Bickford and Rouston of the Khyber Rifles discussed the matter at Landi Kotal. "The construction of the railway will undoubtedly be unpopular" Roos-Keppel wrote[13] to Major WE Venour, staff officer to the Chief Commissioner on 31 May 1905.

The railway would be very exposed to attack, in particular from the north. As a result a levy corps would need to be strong and self contained, with about 1 750 rifles. The Khyber Rifles could be expanded to provide guards, and both the Khyber Pass and the Kabul River Railway could be supported from Landi Kotal, though outposts would be two or three days march over difficult terrain from the garrison. Roos-Keppel suggested that troops' pay may have to be raised. If the line ran via the Loi Shilman valley then the Khyber Rifles would need six additional infantry companies, with 100 Sowars (cavalry). The more exposed Kabul River route would require nine infantry companies, with 100 Sowars.

The line was to be protected by blockhouses. On the Loi Shilman route the locations of the defensive points would be:

- Blockhouse 1: 1 mile north west of Shahmansur Khel, to control the Chena Gudr ferry.

- A signalling post night be required on Tor Ghar, between blockhouses 1 and 2.

- Blockhouse 2: Spur north of and immediately above Ghorangi.

- Blockhouse 3: On main spur due east of the mouth of the Loi Shilman valley.

- Blockhouse 4: 1/2 miles further north

- Blockhouse 5: On hill 1/2 miles north west of Fatteh village

- Blockhouse 6: On hill 1/6 mile north of Kama.

- Blockhouse 7: If politically possible this would be located on the main ridge south of the pass, else it would be on a knoll about 2/3 mile south east of the Shilman Ghakki pass.

The Kabul River alignment would require Blockhouses 4, 5 and 6 to be on the left bank of the river. Number 7 blockhouse would be located either in the same place or further to the west. Two companies would be located from Shinilo Gudr to Sara Tigga. Half a company would be based at Shinpokh, half at Smatsai.

On 6 July 1905 Lieutenant-Colonel HA Deane wrote[14] to the Secretary to the Government of India with "proposals for the protection of working parties during the construction of the railway and for the safeguarding of the line after completion." Deane understood "there is a possibility of work on this railway being put in hand in the coming Autumn".

"Apart from the question of Afghan interference, the line is open to attack from two sides:- the Afridis and other tribes on the right bank of the Kabul River and the Mohmands ... on the left bank." Construction would require "assistance not only of the Khyber tribes through whose country the railway will actually run, but also of the Mohmands who from their position on the flank and their propinquity to the railway up Sara Tigga would be enabled to cross the Kabul River and inflict damage on the line." Because the Afridis and Mohmands were hereditary enemies, Deane did not recommend Roos-Keppel's proposal to use the Khyber Rifles to guard the railway. Instead he recommended a moderate increase in the number of Khyber Rifles to guard the railway within the Khyber agency's area, and the raising of a levy corps of Mohmands to hold a chain of posts from Michni to Sara Tigga.

On 15 July 1905 the British Government sent a telegram to the Government of India saying they were not satisfied that the Shilman Ghakki route was the best available. The Government of India said it would investigate further[15].

Construction work began on the Loi Shilman route, and by 1907 there was 32 km of metre-gauge line from Kacha Garhi on the railway to Jamrud, north along the Kabul River valley and then westwards towards the Loi Shilman valley[16]. The Flying Afridi ran as far as Warsak in the Peshawar plain[17] (not the Warsak in the Loi Shilman valley).

An alliance between Britain and Russia resulted in the Convention of St Petersburg of 31 August 1907[18]. Britain would "neither to annex nor occupy" any portion of Afghanistan, and Russia declared the country to be "outside the sphere of Russian influence". This reduced the perceived threat to India, and the Kabul River railway was dismantled in 1909 without reaching the Durand line. The track materials and bridges were recovered for reuse elsewhere.

After the Third Afghan War (1919), Colonel Gordon R Hearn planned the 1 676 mm gauge Khyber Railway[19] from Jamrud. The Afghan government objected to the British plans, as they were purely strategic and unlikely to ever become part of a commercial link to Afghanistan. Despite this, the line was opened to Landi Kotal on 3 November 1925[20], and was completed to Landi Khana on the Afghan border on 23 April 1926. The final 2 km section to Landi Khana had a downward ruling gradient of 1 in 25, and the railway was equipped with fortified stations. In 1926 tracks were laid up to the border post, but not used. Following requests from the Afghan authorities the section to Landi Khana closed on 15 December 1932.

The line to Landi Kotal still exists, though the weekly service was suspended for some time in 2001-2002 during the US-led war in Afghanistan. Steam hauled services had restarted by April 2002[21].

A Royal Tour

Abdul Rehman's grandson Amanullah became King of Afghanistan in 1919, and began to modernise the nation. His plans included railways.

He began work on a new European-style capital city at Darulaman[22] near Kabul. On 15 December 1922 The Locomotive[23] reported "Travellers from Afghanistan state a railway is being laid down for a distance of some six miles from Kabul to the site of the new city of Darulaman, and also that some of the rolling stock for it is being manufactured in the Kabul workshops."

In 1928 King Amanullah embarked on a seven month tour of Europe, visiting France, Germany, Italy and Britain. In December 1927 the Indian vice-regal train was sent to Chaman to collect him, with two HG/S 2-8-0 locos on the front and two on the back. The King or one of his party pulled the communication cord in Khojak tunnel, causing a coupling to break, and it took 20 minutes to restart the 12 coach train[24].

Railway Gazette[25] reported how the "astute and active potentate" had toured the Great Western Railway's Swindon works on 21 March 1928. "Fresh from an aerial flight over London", King Amanullah went to Paddington station. Here he was received by the "Mayor of Paddington and some of his official brethren, all bravely attired". However "To the great disappointment of many, the King's beautiful consort was not of the party: it was understood that the Royal lady was too fatigued to bear the journey."

The King left Paddington at 13.30, hauled by the locomotive King George V. Luncheon was served during the journey, and the King arrived at Swindon carriage works at 14:55. His Majesty "spent a crowded hour of his glorious sight-seeing life in the workshops"[26]. He departed from the locomotive works at 16:15, arriving back at London at 17:45. To mark the occasion a brochure containing an illustrated history of Swindon works was produced in Persian.

King Amanullah, "with his customary keenness and untiring energy, manifested the liveliest interest in everything he saw." Chief Mechanical Engineer CB Collett was kept busy answering questions through an interpreter. The King inspected the footplate of newly-built locomotive King Charles II. At the close of the tour, a "large number of workpeople" "gave the distinguished visitor three hearty cheers, which seemed to please him". Railway Gazette commented "there are no railways at present in Afghanistan,and it is said that there will not be until Afghanistan herself can build them."

Steam Trams in Kabul

King Amanullah bought three small steam locomotives from Henschel of Kassel in Germany, and possibly either some carriages or underframe components to use with locally-built bodies. The locos were put to work on a 7 km roadside tramway linking Kabul and Darulaman [Map]. In August 1928 The Locomotive[27] reported "the only railway at present in Afghanistan is five miles long, between Kabul and Darulaman."

King Amanullah was later overthrown, abdicating on 14 January 1929. He left Afghanistan, travelling from Chaman on 23 May bound for Bombay. The Kabul locomotives were later put into store in the two-road engine shed. They are now derelict at Kabul museum, in Darulaman; one has been stripped down for scrap materials. In January 2002 museum caretaker Omara Khan Masoudi said[28] "These are historical artefacts and we want to keep them. Of course, it would be good to have a real railway now, that would be progress". In October 2004 the locos were being stored outdoors.

Ambitious Proposals

In the August 1928 report The Locomotive[29] said "Following King Amanullah's visit to Europe, agents of American, French and German firms were invited to Kabul to make surveys for the construction of roads and railways. It is now announced that the Lenz company of Berlin, has secured an option on all public railway construction and operations in Afghanistan."

The first section of German-built railway was to have linked Jalalabad with Kabul, eventually connecting to the Indian system at Peshawar. Lines to join Kabul with Kandahar and Herat would follow later[30].

A French syndicate headed by arms dealer Sir Basil Zaharoff agreed to survey the route of a railway from Kabul to Kandahar, to be followed by an extension to Herat, in Summer 1928. A team of engineers was assembled, headed by Michel Clemenceau and Pierre Makecheef. The British government arranged for Zaharoff and Clemenceau to keep them informed of developments, and in September they told the British embassy in Paris that they had surveyed the Kabul to Herat route[31]. In February 1929 Michel Clemenceau returned to Kabul to continue working on the scheme.

Following the overthrowing of Amanullah, in March 1930 Railway Gazette said[32] "It is reported from Calcutta that a contract given some time ago to a German firm for the construction of the first railway in Afghanistan has been confirmed by King Nadir Shah, and that a delegation of engineers will shortly be leaving Germany for Kabul. The plans provide for ultimately connecting the main line from Kabul with Russian railheads at Kushka and Termez, while another line will link Kandahar with Chaman and Quetta."

Questions were raised about this contract in the House of Commons[33]. Mr Freeman asked the Secretary of State for India whether the government had been officially advised or consulted with regard to the contract with a German firm for a railway between Kabul and Torkham, the last Afghan post on the Indian frontier; if the proposal contemplated the connection of the main line from Kabul with Kushk and Termez; and whether the government of India had communicated to him their observations on the proposal. Mr Wedgewood Benn replied "I have no official information of the existence of any such contract, though I have seen the newspaper report to which my honourable friend no doubt refers."

In November 1930 the Reuters Teheran correspondent reported that King Nadir Shah had endorsed the German contract[34]. In July 1932 The Western Mail reported that an ambitious scheme current since 1928 proposed a Kabul to Jalalabad line, then a link to Torkham on the Indian border[35]. A line of about 523 km would link Kabul with Kandahar via Ghazni, and a further line would be built between Kandahar and Herat. The line from Kabul would eventually be extended to meet the Russian railhead at Kushk and Termez, providing a through rail route between Europe and India.

The Afghan government approached the Japanese Railway Department to supply engineers and investment of ¥50m for the 1600 km scheme. The request[36] followed successful Persian and Soviet employment of Japanese engineers.

In January 1932 Northern News Services Ltd reported that King Nadir Shah had approved a new railway scheme[37]. This would run from the Khyber Pass, through Jalalabad to Kabul, and then to Kandahar and Chaman, with a subsidiary line from Chaman to Herat. The total length would be 1440 km, and heavy engineering works would be needed. The line was planned as metre gauge, but the Indian 1676 mm would be considered "if it is found not to be very much more expensive". The government hoped to use motor transport to provides links with important centres not on the rail network. According to Railway Gazette, "the only railway in Afghanistan at the present time is a line about two miles long at Kabul, but this is little more than a tramway and service is intermittent". This suggests the Amanullah's tramway was still operational, though perhaps truncated.

Later the same month it was reported that an agreement had been signed between representatives of Russia, Persia and Afghanistan, and Japanese financiers for a line linking Russia with India[38]. "The report gives strength to the opinion that the Soviet government has given Japan a free hand in Manchuria in return for Japanese financial support of Russian enterprises in the East."

None of these lines were built.

Industrial Diesels

In the 1950s a 22000 kW hydroelectric power station was built at Sarobi, east of Kabul, with the aid of German expertise. Three Henschel four-wheel 600 mm gauge diesel hydraulic locos built in 1951 (works numbers 24892, 24993, 24994)[39] were supplied to the power station. The fate of these locomotives is unknown.

In 1979 mining and construction locomotive builder Bedia Maschinenfabrik of Bonn supplied five D35/6 two axle diesel-hydraulic 600 mm-gauge locomotives, works numbers 150-154, to an unknown customer in Afghanistan[40].

International Plans

In the early 1950s a scheme existed to build a new road from Kabul northwards to the Hindi Kush, by way of the Salong Pass. This hugely expensive and technically difficult scheme would have involved a 8.5 km tunnel and a series of approach tunnels. Snow would have made the road impassible in winter. According to MER Lingeman[41], the British ambassador in Kabul, one suggestion "which held the field for some time - Ismail Khan [Governor of Kataghan & Badak Inshan] spoke of it quite seriously to me - was that the greater part of the tunnelling could be avoided by a funicular railway, but the consequent need for double unloading seems to have led to this solution being discarded."

In 1952 the British Embassy in Washington found[42] that the US State Department was proposing to tell the Afghan government that if the Afghans were prepared to be accommodating in their desire to take Pakistani territory to form a Pathanistan, the USA would be interested in helping with the construction of a Quetta to Kandahar rail link, doubling the partly-single line to Chaman, and negotiating for Afghanistan "transit in bond facilities by that route."

BAB Burrows, British Ambassador in Washington, thought the USA was looking at the issue from a purely economic point of view, and had not considered the political implications of building such a line. Moscow might claim a "right to a line to extend to Herat the existing Soviet line which finishes at Kushka." In the South East Asia Department of the Foreign Office JG Tahourdin thought the practical difficulties would be so great that the Soviet reaction "need hardly be advanced as additional arguments against the project". The Foreign Office's "preliminary reaction therefore is to regard the suggested railway extension as a very doubtful starter".

The British military attaché in Kabul had asked his "painfully naive" US counterpart Colonel Mackenzie if Russian objections had been considered when the USA offered its support [43]. When the potential of a Soviet line to Herat was mentioned "The gallant Colonel sat up and exclaimed, as the light dawned on him : 'Oh, then there would be trouble.'"

In 1966 plans were drawn up for a short cross-border extension of the Chaman line. That September Railway Gazette reported[44] "Work on the proposed rail link between Chaman in Pakistan and Spin Baldak in Afghanistan is to begin soon and will take about a year and a half to complete. The link will be over seven miles long and will cost about $800 000. Over two miles of the link will be in Pakistani territory." The line was intended to provide a route to Karachi, and unlike the Khyber Pass route would not need reversing stations. The line is shown on some maps[45], but was not built.

In March 1972 Railway Gazette reported[46] Iranian proposals for an extension from their railhead at Mashhad to Herat.

Grand Projects

In 1975 a team of Indian railway consultants surveyed 1 400 km rail network linking the cities of Herat, Kandahar and Kabul[47]. Feasibility studies were carried out using a US$20m loan granted by Iran[48], and a representative of Rail India Technical & Economic Services (RITES) attended inter-governmental meetings. Estimated to cost between Rs8 000m and Rs9 000m, the network was to be based on a northwest to southeast main line. This would run from the 1 435 mm gauge Iranian line at Mashhad, through Herat and Kandahar to Chaman in Pakistan, giving access to the port of Karachi. A line from Herat would meet the 1 524 mm gauge line at Kushka in the USSR (now Turkmenistan). A line from Kandahar would serve Ghazni and Kabul. The line to Chaman would provide access through Pakistan to Zahedan in Iran, terminus of a 1 676 mm gauge line from the Pakistani rail network, but isolated from the Iranian rail network. From Zahedan a 1 435 mm gauge Iranian line was planned to Kerman and the Persian Gulf port of Bandar Abbas. The May 1975 issue of Railway Gazette International commented "there will be certainly be some difficulty over choice of gauge".

In 1976 the Afghan government's seventh national plan (covering the years 1976-80) approved a scheme drawn up by French consultants Sofrerail for a 1 815 km, 1 435 mm gauge railway system[49]. Finance was to be provided by Iran, which stood to benefit from transit traffic. The line would have linked with Iranian State railways at Mashhad, crossed the border at Islam Qala, then gone on to Herat, Farah and Lashkar Gah, Kandahar, copper mines in Logar province, Ghazni and Kabul. A Kandahar to Chaman line would have provided the link to Pakistan for traffic to the Arabian Sea at Karachi. The Herat to Kushka line was not included, but a line from Lashkar Gah to Tarrkum and then across the Iranian border to Kerman was planned. This would give access to Bandar Abbas. A branch would serve iron ore mines near Bamiyan, northwest of Kabul[50].

A maximum speed of 160 km/h was proposed, with longer term plans for lightweight trainsets to run at 200 km/h. Around 75% of the network would have a minimum curve radius if 2 km and a maximum gradient of 1%. The rest of the network would have 1.5% gradients and a maximum speed of 100 km/h. UIC 45 kg/m continuously welded rail on tied-block sleepers was planned, with signalling installations backed by train radio. Kandahar would have a control centre, marshalling yards and a motive power depot and workshops. An initial fleet of 40 locomotives was planned, with provision for 65 more. Due to the high altitudes power output loses of 22.5% were expected from the 2400 hp diesels. 2 400 staff would be required in 1975, and an ultimate total of 3 300 was envisaged. Traffic forecasts predicted 1 300m passenger-km and 1 300 tonne-km in 1985. A 100 km cableway was planned to link iron ore deposits at Hajigak in the Hindu Kush mountains with a railhead, from where ore would be taken to Iranian steel works.

The US$1.20bn[51] plans were abandoned following the communist coup in Afghanistan 1978, and the Iranian revolution.

Soviet Extensions

During its military involvement in Afghanistan the USSR extended two 1524 mm gauge railway lines to carry troops and military supplies across the Amu-Darya river, which formed the Soviet-Afghan border.

A 15 km line was built from Termez in Uzbekistan to a transhipment point at Kheyrabad, near Hariatan on the south bank of the river. Termez has rail access eastwards to Dushanbe in Tadzhikistan, and westwards via Kerichi in Turkmenistan to the Uzbek cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.

Work on a 34m rouble combined road, rail and oil pipeline bridge began with the Soviet intervention in the winter of 1979-1980. An agreement for use of the 1000 m "Friendship Bridge" was reached between the Afghan and Soviet authorities in May 1982[52], and it opened that June. The bridge strengthened the strategic transport capabilities of the USSR by establishing a railhead on the south side of the river, and so early in 1985 Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence began to formulate plans for Mujahideen fighters to destroy it[53]. The CIA provided advice on the types of explosives needed, and where they should be placed to demolish two or three spans. To obtain maximum benefit from the current flows in the Amu-Darya the underwater demolition operation was planned for the summer. A team of troops was to practice the assault on an Afghan dam. The CIA did not supply good reconnaissance photographs of the bridge, so local commanders provided details of the sentries and company post on the Afghan end of the bridge, and an APC permanently on duty. Later in the year the President of Pakistan vetoed the proposed assault, fearing reprisal attacks on vital bridges in Pakistan.

The Kheyrabad line was planned to form the first stage of a 250 km 1 520 mm gauge railway to Pul-i-Khumri, 150 km north of Kabul[54]. From the Amu-Darya river crossing the railway was to have run southwest to Kholm, east towards Kunduz and Khanabad, then would climb south through Ab Kul and Bahlan, and reach the Surkhab river valley and a military supply depot at Pul-i-Khumri[55] in the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains. The second stage of the extension plans would have taken the line to Bagrami air base, then on to Kabul. The complete line to Kabul was expected to cost 3.1bn rubbles.

In April 1983 a Modern Railways correspondent[56] reported that the Soviet-backed Afghan Government had contacted the Economic & Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) seeking financial and technical assistance for a rail network. This was to link Kabul, Kandahar and Herat. Pakistan and Iran would be reached by Kandahar to Chaman, and Herat to Islam Qala branches. However neither country's government recognised the existing Afghan regime. Surveys drawn up by a Franco-German consortium in 1928 were presented. ESCAP sent two missions, including railway experts, to Afghanistan.

The second Soviet line into Afghanistan ran for 9.6 km from Kushka in Turkmenistan to Towraghondi. Railway lines ran parallel to the Amu-Darya on the Soviet side, and there were subjected to cross-border sabotage and military attack during the war. Both lines fell out of use with the Soviet withdrawal in 1989,and Uzbekistan closed the Friendship Bridge on 24 May 1997, following the rise to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Foreign Advice

In 1992 plans were announced[57] for Pakistan Railways engineers to survey a possible 800 km route from Pakistan to Tadzhikistan, via Jalalabad and Kabul. PR's General Manager was reported in the newspaper Dawn as saying it was in Pakistan's national interest to establish links with the recently independent central Asia republics via Afghanistan rather than Iran.

In 1999 the Bakhtar news agency in Kabul[58] told the BBC that a Canadian team had held talks in Kabul with the Construction Minister and other officials regarding the construction of airports, roads, and railways. Bakhtar's Muhammad Naeem said a Canadian team would carry out a survey and feasibility study.

Re-opening for Aid

On 9 December 2001 Uzbekistan re-opened the Friendship Bridge across the Amu-Darya, following talks between US Secretary of State Colin Powell and Uzbek President Islam Karimov[59]. On 8 December 2001 Colin Powell told reporters the bridge "will ease the humanitarian situation considerably".

The bridge forms the only land link between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, and President Karimov was reported to be reluctant to open the bridge owing to worries about incursions by fleeing Afghan combatants. It had been reported that the Afghan side of the bridge had been mined, but US military engineers found it to be safe for use.

15 vans of flour were brought into the country on 9 December. The locomotive used for the aid train was 3199, a Class TEM1 Co-Co. This class was developed from 1958, based on Alco designs supplied to the USSR in 1944-45.

Plans Resurface

Proposals to revive the 1970s railway schemes were put forward at the International Conference on Reconstruction Assistance to Afghanistan, held in Tokyo in January 2002[60]. A 1 810 km line would run from Herat to Kandahar, and north to Logar and Kabul, linking Afghanistan with Bandar Abbas in Iran and giving access to Pakistan. "We can't say what it would cost now because we haven't done an up to date feasibility study yet" Afghanistan's Deputy Planning Minster Abdul Salam told Reuters[61]. "The world is coming together now and we want to be part of this world".

On 28 February 2002 Iranian MP and Chairman of the Iranian-Afghan friendship group Gholam-Heydar Ebrahimbay-Salami announced that Majlis (the Iranian parliament) had allocated $25m in its 2002 budget bill for the construction of a railway line from Torbat-e-Heidarieh in Khorassan province, through Afghanistan's Samangan province to Herat[62]. Finance would come from international aid and funds from the Iranian Commission for the Reconstruction of Afghanistan. The MP said the railway would give Afghanistan access to the Iranian and European rail networks. "This plan will be implemented along with the Kabul - Paris and Kabul to China rail network construction plan whose preliminary studies were made in 1975 by a French company" he explained. Iron ore would be carried[63].

Stocklist

| Type | Builder | Gauge | Wheel arrangement | Build date | Works no. | Location | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam | Henschel | 2ft6in | 0-4-0WT | 1923 | 19680 19681 ??? |

Kabul Museum | Still extant October 2004 |

| Diesel hydraulic shunter | Henschel | 600 mm | 4w | 1951 | 24892 24993 24994 |

Supplied to Sarobi power station | Unknown |

| Diesel-hydraulic | Bedia Maschinenfabrik, Bonn | 600 mm | 4w | 1979 | 150 151 152 153 154 |

Unknown | Unknown |

| Diesel hydraulic | Eastern Bloc? | Approx. 600 mm | B-B | Carried numbers TIJ 1 TIJ 2 TIJ 3 TIJ 4 |

Reported[64] at Tang-i-Jharoo, between Kabul and Khyber Pass 1969-03-15 | Unknown |

References

The links to other websites here are those I used when writing this history, and may now be out of date. The pages may no longer exist, or their content may have changed.

1 Railway Directory 2001 Chris Bushell (Editor)

2 CIA World Fact Book http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/

3 Couplings to the Khyber PSA Berridge 1968

4 England & Afghanistan Dilip Kumar Ghose 1960

5 Railways At War John Westwood 1980

6 Reform and Rebellion in Afghanistan 1919 - 29 Leon B Poullada

7 Afghan rail plan among proposals for donors CNN News report, from Reuters 2002-01-21

8 The Transcaspian Railway and the Power of the Russians to Occupy Herat Captain AC Yate 1891-04-29 PRO WO 106 178

9 Baluchistan to Russia railway map http://users.ev1.net/~jtslrr/1910h46.jpg

10 Afghanistan: Military aspect of Railway communication between Europe and India - Russian aspirations towards Afghan-Turkestan 1911, PRO WO 106/58

12 Mentioned in Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel HA Deane to the Secretary to the Government of India 1905-07-06 PRO 106/56

13 Letter from Major GO Roos-Keppel to Major WE Venour 1905-05-31 PRO WO 106/56

14 Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel HA Deane to the Secretary to the Government of India, 1905-07-06 PRO 106/56

15 Proposals for raising a levy corps of Mohmands and increasing the Khyber Rifles to guard the Kabul River Railway. Lettre from EHS Clarke, Deputy Secretary to the Government of India, to the Hon'ble Mr MF O'Dwyer, officiating Chief Commissioner and Agent of the Governor General in the North West Frontier Province. 1905-08-28 PRO WO 106/56

16 Couplings to the Khyber PSA Berridge 1968

17 Gun Running & the Indian North West Frontier Hon. Arnold Keppel 1991

18 Key Treaties for the Great Powers 1814 - 1914 Vol 2 1871 - 1914 Michael Hurst (Ed.) 1972

19 Couplings to the Khyber PSA Berridge 1968

21 Daily Telegraph 2002-04-05 http://dspace.dial.pipex.com/steam/trains/pakist03.htm

22 Dawn of another era Railway Gazette International p317 August 1976

23 The Locomotive Magazine p379 1922-12-15

24 Couplings to the Khyber PSA Berridge 1968

25 Afghan King's visit to Swindon works. (Includes a copy of the timetable, in English and Persian) Railway Gazette p438 1928-03-23

26 Afghan King's visit to Swindon works. (Includes a copy of the timetable, in English and Persian) Railway Gazette p438 1928-03-23

27 The Locomotive Magazine p262 1928-08-15

28 Afghan rail plan among proposals for donors CNN News report, from Reuters 2002-01-21

29 The Locomotive Magazine p262 1928-08-15

30 Projected Afghan railways Railway Gazette International p686 November 1930

31 1928-09-18 IOL, LPS/10/1928 Afghan series Serial no 117, reference in Reform & Rebellion in Afghanistan 1919 - 1929 Leon B Poullada

32 Railway Developments in Afghanistan Railway Gazette p439 1930-03-21

33 An Afghanistan Railway Questions in Parliament Railway Gazette p826 1930-05-23

34 Projected Afghan Railways Railway Gazette International p686 November 1930

35 Railway Development in Afghanistan Railway Gazette p141 1931-07-31

36 Japanese Engineers for Afghan Railways Railway Gazette p382 1931-09-18

37 Railway Development in Afghanistan Railway Gazette p61 1932-01

38 Afghan Railway Scheme Railway Gazette p164 1932-01-29

39 Industrial locomotives: India/South Asia. Simon Darvill, http://www.geocities.com/irfca_faq/misc/industrial/Afghan.html

40 http://www.rinbad.demon.co.uk/2002q1.htm data from Lokomotivfabriken in Deutschland CD, available from http://www.lokhersteller.de/ but not seen by Andrew Grantham

41 Confidential report by air bag from British Embassy in Kabul 1953-01-08 PRO FO 371/106668

42 Letters between the British Embassy in Kabul, the South East Asia Department of the Foreign Office and the British Embassies in Washington and Moscow, December 1952, January 1953 PRO FO 371/106668

43 Letter from MER Lindeman to J Dalton Murray, South-East Asia Department, Foreign Office, 1952-03-28 PRO FO 371/106668

44 Focus: Africa & Asia Railway Gazette p675 1966-09-02, p. 675

45 Times Atlas 1990.

46 Afghanistan link proposed by Iranian Railways Railway Gazette International p85 1972-03

47 India surveys 1 400 km network in Afghanistan Railway Gazette International p167 May 1975

48 India surveys 1 400 km network in Afghanistan Railway Gazette International p167 May 1975

49 Afghan network of 1 815 km goes ahead Railway Gazette International p204 June 1976

50 Afghan rail plan among proposals for donors CNN News report, from Reuters 2002-01-21 http://europe.cnn.com/2002/WORLD/asiapcf/east/01/21/afghan.rail/index.html

51 Afghanistan - a Country Study Area Handbook Series, 5th edition 1986

52 USSR - Afghan link Modern Railways p342 1982-08

53 Afghanistan - The Bear Trap - Defeat of a Superpower Brigadier Mohammad Yousaf (1992, 2001 edition used)

54 Kabul to be linked to Soviet Railways Railway Gazette Internationa p236 April 1983

55 Afghanistan - a Country Study Area Handbook Series, 5th edition 1986

56 Rail links with Pakistan and Iran Modern Railways April 1983

57 Rail survey in Afghanistan Modern Railways November 1992

59 Uzbek bridge opens for aid to Afghanistan. News report from Yahoo.com 2002-12-09

60 Russian-language news report from http://www.mps.ru 2002-01-22

61 Afghan rail plan among proposals for donors. CNN News report, from Reuters 2002-01-21

62 Allocation of $25m for Afghan rail link Nimrooz newspaper http://www.nimrooz.com/html/677/16125.htm 2002-02-08

63 The Iran-Afghanistan Railway will be constructed. Raja Trains website http://www.rajatrains.com/english/news&facts/briefnewsdetails.asp?id=5&IsArchive=-1 2002-03-10

64 Afghanistan: A Railway History Dr Paul E Waters 2002

A rough map showing, with no claim to accuracy, the approximate routes of railway schemes proposed for Afghanistan.

The Kabul to Darulaman Tramway

(The following paragraphs are condensed extracts from Andrew Grantham's web page on the Kabul Tramway.)

A 2'6" gauge tramway ran for about 7km from Kabul southwest to Darulaman. It had two 0-4-0 well tank locomotives, built by Henschel in Kassel as works numbers 19680, 19681 of 1923. A third loco of approximately 60cm gauge has also survived at Darulaman.

Despite everything, the steam locos have survived, at first in their shed at the Kabul museum in Darulaman, and now out in the open. On October 13 2004 Wim Brummelman found three locos at Darulaman, in the yard behind the museum! Most sources had suggested there were only two locos. All three would appear to be the same type, presuambly Henschels.

Appendix

History of this web page

2002-06-18. Webpage created

2002-07-03. Map page added.

2002-08-29. Iran-Afghanistan reports added.

2002-10-06. Henschel works numbers added from Continental Railway Journal no. 131 (Autumn

2002). News page created.

2003-01-27. It seems pretty certain that the Kabul Henschel locos are 2'6" gauge, rather than metre gauge, so

I've changed the table.

2003-02-25. Cosmetic changes.

2003-03-02. More info added to the Kabul tramway and stocklist sections.

2003-05-29. Cosmetic changes.

2005-01-16. Kabul loco photos added.

2006-11-10. Version of web page added to IRFCA.org by generous permission of Andrew Grantham.